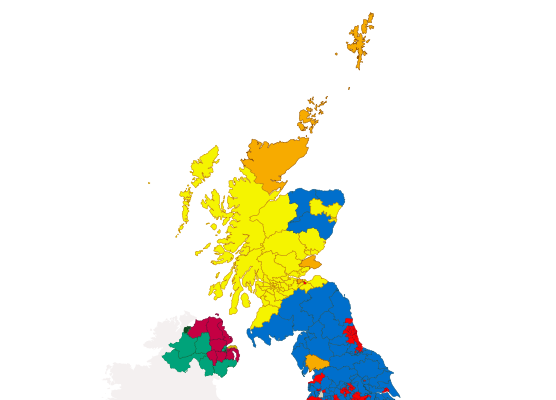

The 2019 UK general election confirmed the divided nature of politics, the demise of British-wide politics and the emergence of a four-nation political system.

The Tories were elected on a 43.6% UK vote made up through winning England with 47.2%, finishing second in Wales with a respectable 36.1%, while achieving second place in Scotland with 25.1%, losing votes and seats.

England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland increasingly march to different political beats. This is the third election in a row in which a different party has won each of the four nations.

The SNP have been the dominant party in Scotland since 2007 and at Westminster since 2015 – having won three Scottish Parliament elections and three Westminster elections in a row. In this election, the party won 45% of the vote, its second highest vote at a Westminster contest. It won 48 seats – taking seven from the Conservatives, six from Labour – reducing it to the sole one held by Iain Murray – and one from the Lib Dems, taking the scalp of Jo Swinson, while losing Fife North East.

What the Scottish result confirms is the deep seam of difference, autonomy and centre-left values which informs party politics. The SNP ran a campaign on three fronts – stopping Brexit, stopping Boris Johnson, and affirming Scotland’s right to determine its own future.

The Tories after Ruth Davidson were expecting grim times and felt some relief only losing just over half their seats. The Lib Dems, despite losing Jo Swinson, ended up with what they started with – four seats. But by far the most disastrous election campaign was that of Scottish Labour (something the party is now making a habit of) going from seven MPs back to one – its paltry total in 2015.

Scottish Labour’s campaign didn’t seem to stand for anything. It was not Corbynite. It wasn’t anti-Corbynite. It wasn’t old Labour and nor was it radical and vibrant. The party has now been in opposition in the Scottish Parliament since 2007 and seems to have become comfortable in the worst of all worlds. It has become acclimatised to losing, but not adapting, to the politics of opposition. It has not yet been able to make the shift from insider to insurgency politics and to make any impact in challenging the SNP as the new establishment.

There is a long tail to this, analysed by Eric Shaw and myself in ‘The Strange Death of Labour Scotland’, about a party that became an entrenched, self-interested, complacent, insular establishment.

When Labour legislated to set up the Scottish Parliament in 1999 many in the party felt this would institutionalise and make permanent the party’s dominance north of the border while giving it even more powers of patronage and preferment. Although Labour never found a governing credo or statecraft for the Parliament and devolution, given how deep the entitlement culture ran in the party, it still found it surprising when voters turned to the SNP in 2007.

Twenty years of the Scottish Parliament has seen nine leaders for Scottish Labour. After Donald Dewar was Scotland’s first First Minister some of these politicians have passed through this post without being noticed or remembered.

The party is still not fully autonomous – despite numerous reviews of its powers and structures. This leads to the ridiculous position in elections where the leader – Richard Leonard in the latest contest – has to defend positions not of his making such as the UK party’s pro-Trident stance and convoluted position on any future independence referendum. This left Leonard, pro-CND, anti-independence and against compromise with the SNP, looking powerless and ridiculous.

More damning, what the party cares for and represents has become ambiguous, blunted by years of being a dominant party, followed by opposition and decline. As the years of devolution have accumulated so the sum total of negligible Labour contributions has become even more paltry – and in the opposition years next to nothing. Six Labour leaders have tried to reinvent the party since 2007 with overall little impact.

The cumulative effect of this was a vote of 18.6% last week – down from 27.1% in 2017 – and the lowest share of the vote since 1910 when Labour was barely a British-wide party. On its current trajectory the party is inexorably heading towards further marginalisation and ultimately irrelevance.

There are few comparisons for a centre-left decline so steep and pronounced – with only the Greek PASOK’s in unique circumstances having fallen more. In terms of attitude, and refusing to change and reform, the dogma of the French Communist Party – once revered and feared in equal measure – has many similarities including a culture of aged miserablist men reminiscing about the golden age of left authoritarianism when they mattered.

Scottish Labour’s long decline is widely commented upon in its former heartland but is often celebrated with glee by many SNP and independence supporters, such was the historic rivalry between the two parties. Yet what this attitude ignores is the wider cost to Scotand of Labour’s decline – leaving aside its impact on the broader Labour alliance.

Scottish Labour’s descent has left the SNP’s ‘big tent’ centrism straddling and dominating Scottish politics. For all of SNP leader and First Minister Nicola Sturgeon’s undoubted skills and authentic cut-through – speaking for Scotland’s centre-left majority opinion way beyond the appeal of the SNP – there is a blurred edge to the SNP’s agenda beyond the ultimate aim of independence.

Despite the social democratic impulse at the heart of the SNP it has been able to offer an ‘all things to all people’ style politics on the domestic front, trying to mitigate Westminster welfare policies while keeping business and corporate interests happy and not offending even the landed aristocratic class. It is an approach they have mostly carried out successfully, but one significant factor in this has been the absence of a serious electoral force to their left, itself aided by the decline into near-impotence of Labour.

Scottish politics is crying out for the political space to the left of the SNP to be given voice and influence. The Greens cannot provide it and pro-independence radical currents around RISE and Common Weal are too small with too narrow an appeal. That leaves an opportunity for Scottish Labour and the possibility of a constituency and impact.

In the days after the 2019 election senior Scottish Labour figures have at last begun an open debate on independence. People such as former MP Paul Sweeney and current MSPs Neil Findlay and Monica Lennon are advocating that the party champion the Scottish Parliament’s right to decide whether there is another indyref – and not leave it in the hands of a Westminster veto.

This seems the beginning of a welcome and overdue shift in Labour: positioning the party on the side of Scotland’s right to self-determination, breaking with dogmatic unionism and refusing to side with Tory intransigence and Westminster minority rule – while not meaning the party becomes pro-independence.

Scottish Labour has fallen far and any road back will be long and painful with success not guaranteed. Yet, in the last couple of days Scottish Labour politicians have begun to show a grasp of the need to change to a political culture which is defined by the constitutional question. In so doing they have aided the day that the same politics will ultimately not be about who speaks for Scotland, but what kind of Scotland we live in, advocate and nurture. That small step could turn out to be a significant one.

Gerry Hassan is a writer and academic and author and editor of numerous books on Scottish and British politics including ‘The Strange Death of Labour Scotland’ and the just published ‘The People’s Flag and the Union Jack: An Alternative History of Britain and the Labour Party’.