The crisis reveals much and will change more – for good or bad. Everything feels like it is now up for grabs. There is much pain and suffering and our hearts goes to out to everyone who is struggling. But so much that is good is being revealed and created. Our interconnectedness, the way tech binds us together, the role of the real key workers and carers, and the rise of the mutual aid movement.

The crisis is a moment to dream and hope – for society to start again and #BuildBackBetter. We wanted to use the moment to look at reasons for hope. Where could we go now? A time to think beyond the usual limits – to spell out what could be. Over the next few weeks we will publish batches of short articles of outrageous hopefulness. Not because we think it will be easy but because everything that ever was starts with an idea, a dream.

After this series on what, we will turn to the question of how. Just like there is no crash or tech determinisms – neither can there be a virus determinism. Everything is down to the right political actions, decisions and behaviours.

But we start now with the why – the reasons for hope.

Click the links to jump to contribution.

Deciding and Doing

- Caroline Lucas – The Reform of Parliament

- Jon Alexander – Deciding together: Democracy as Participatory

- Su Maddock – Female Leadership

- Lauren Roberts-Turner – Young People and the Lockdown

Loving and Living

- Laura Parker – Love is all you need

- David Robinson – Relationships

- Hugo Dixon – Meaning

- Robert Phillips – Trusting Each Other

Adapt, Adapt, Adapt

- Anthony Painter – Embracing and adapting to vulnerability

- Layla Moran – A Basic Income for All

- Fernanda Balata – Building better with nature

- Frances Foley – Versatility and Value

- Sue Goss – Resilience from diversity

- Tom Schuller – Lifelong Learning

Solidarity

- Ruth Lister – An End to Poverty?

- Zoe Gardner – Immigration

- Isaac Stanley – Valuing the Undervalued

- Francesca Klug – The Rehabilitation of Universalism?

- Sue Tibballs – The Social Sector

- Danny Sriskandarajah – Caring for carers

Business as Usual?

- Loughlin Hickey – Better Business

- Christian Wolmar – How We Move

- Shuvo Loha – Work, Fulfilment and Obligation

- Martin Yarnit – A better way of farming and shopping

- Fran Boait – Public health before private wealth

- Jesse Griffiths – The transformation of finance

Deciding and Doing

Caroline Lucas is the Green MP for Brighton Pavilion

I’ve been pushing for Parliament to move into the 21st century ever since I was first elected in 2010. Maybe a virus which echoes the global pandemic of 1918/19 will help achieve that.

We could start by moving out of the Palace of Westminster, rat-infested, sinking into the Thames and – according to Imperial College scientists – a breeding ground of coronavirus. How symbolic. It’s always stood for what is broken about our politics. So, let’s take this opportunity to move Parliament out of London.

Seeing the screens perched around the House of Commons for the first sessions of the virtual Parliament underscored how unsuitable the chamber is for a 21st century parliament. Using video-link technology while still observing the arcane rituals and language of the House jarred. But, nevertheless, these virtual sessions have been a leap forward. The handful of MPs in the House of Commons, sitting the required two metres apart, have been joined by many others (including me) via video link, able to question ministers directly. It’s not ideal sitting in a Zoom “waiting room” until you are called, but at least you know you will be. MPs can often waste hours in the chamber hoping to catch the Speaker’s eye without success. Select committees are also carrying on via video link, so they can continue their important job of scrutinising legislation and policy and holding government ministers to account.

But building back better means more than just minor adjustments to parliamentary procedure. The whole system needs an overhaul, starting with the House of Lords. All that theatrical ermine, and seats reserved for hereditary peers. It has to go and be replaced with a fully elected, properly representative second chamber.

And while we’re about it, let’s change the voting system too so that two thirds of voters don’t see their vote wasted. A fairer voting system which properly reflects the range of views in our society and parties which discuss and work together, rather than hurl insults across a chamber, is how to run a country.

Keeping our democratic processes ticking over during this coronavirus lockdown has forced Parliament to put a toe into the 21st century. It’s time we dived right in.

It was only until recently that there was no method of voting electronically, which meant that many important Bills, were not put to a vote.

If we do establish a more permanent move to electronic voting, then I hope that it will put an end to the archaic practice of division bells ringing across the Palace of Westminster, forcing MPs to stop whatever they are doing and run from wherever they are on the parliamentary estate to the chamber in the eight minutes allowed. Speeding up the voting process won’t just be more efficient, it would also mean all amendments to legislation could be put to a vote – which doesn’t happen now because there simply isn’t the time.

If this virtual Parliament speeds up the transition to a more efficient parliamentary system, then that can only be a good thing. Those who believe they are protecting tradition and heritage by defending so many old-fashioned procedures are instead damaging our democracy.

With so many people, who are able to, working from home and joining colleagues via video link, perhaps seeing MPs joining a debate in the same way will create a sense of connection between MPs and voters which has been sadly missing in recent years. Next we need to tackle the arcane language.

But at least MPs are now able to hold the government to account over its handling of the biggest health crisis to face this country for a hundred years. And that can only be a good thing.

Deciding together: Democracy as Participatory

Jon Alexander is co-founder of the New Citizenship Project, a consultancy working to build a more participatory society, and a member of the OECD Innovative Citizen Participation Network.

Participatory democracy puts the demos, the people, back into demo-cracy. It has been taking shape around the world. It is what communities, regions, nations and indeed the world will need in a Covid-19 world, and this will be the trigger for it to arrive fully in the mainstream of our politics.

The concept of participatory democracy represents a whole range of approaches, from open idea generation which seeks to harness the energy and ideas of citizens right at the start of policy development; to participatory budgeting whereby citizens hold decision making power over the allocation of public money; to deliberative processes where representative groups of citizens (sometimes called “mini publics”) come together to develop recommendations for government interventions – or even write laws themselves.

This more authentic form of democracy is ripe for wider adoption. Over the last decade, it has been taking shape around the world. Madrid created the most ambitious climate strategy of any city in the world by aggregating ideas put forward by its citizens; Ireland made access to abortion legal up to 12 weeks on the recommendation of a Citizens Assembly of 99 of their own, selected at random; Taiwan has developed a pioneering settlement with Uber through the use of a consensus building process involving every stakeholder group from drivers to passengers to government administrators as peers and collaborators. One experiment even brought together 526 American citizens, representing the full diversity of that famously divided nation, and found a remarkable degree of common ground as to what could and should be done. The list could go on.

Covid-19 will be the trigger for this wider adoption. This pandemic is already creating a step change in the difficulty of the decisions and trade-offs required in democratic decision-making, and that will only increase: the demands of the economy will need to be balanced with short-term public health; contact tracing will require the balancing of privacy and security; we may need to discriminate between what different people can do based on age and even immunity status. The decisions made will have to be accepted as legitimate in a deeply divided society. Participatory democracy approaches are uniquely equipped to answer these challenges, because they involve citizens directly in a way that both results in better decisions and in doing so builds understanding, empathy and legitimacy. This truth will create the demand that will accelerate its arrival into the mainstream.

What will that look like in practice? It could start with a Citizens’ Convention on the transition from lockdown (as proposed by Matthew Taylor of the RSA); it may initially take a more limited form on specific issues. It could (and I would argue should) go as far as replacing the House of Lords with a standing Citizens’ Assembly, analogous to what is in place in Belgium; it might look more like Reykjavik’s ongoing channel for the ideas of citizens to shape their city. Participatory democracy could come in many different shapes and sizes. But it’s coming.

Su Maddock is a feminist psychologist working to transform the state and the economy through women’s leadership, mutuals and local action.

Covid-19 has shone a light on women’s political leadership across the world. Many commentators have noticed that it is women leaders who are handling the crisis with compassion and decisive action – and their calm leadership has become the news.

New Zealand PM Jacinda Ardern led an early lockdown in March with extensive testing and tracking. She was not afraid to take swift action and gained support because of her clear and empathetic public messages – this was a woman who, has taken a pay cut and anticipated the need for education packs for parents after school closures.

Angela Merkel, the Chancellor of Germany was never in denial about Covid-19 and recognised it could infect up to 70 per cent of the population. She reassured Germans because she had a plan for testing and tracking the virus through a well-equipped health service and understood the need to mobilise local health services to track those affected in communities. This reduced the number of deaths in Germany.

Tsai Ing-Wen, the prime Minister of Taiwan was one of the first to notice the virus, in January, and immediately led speedy testing and tracking which controlled its spread; her country is now exporting science and protective kits to Europe and the USA.

Mette Fredericksen in Denmark, Katrin Jakobsdottir in Iceland, Erna Solberg in Norway, Sanna Marin in Finland and Nicola Sturgeon in Scotland have all burst into national political leadership in Northern Europe.

These women, value people and science, understand supply chains and the importance of telling the public the truth. Their connection with the public while also anticipating risks and valuing the contribution of others is what allows them to have confidence in their own judgment.

They are not populist leaders who follow the pack rather than lead. This is in contrast with their male counterparts in the USA, UK, India and Australia where macho cultures dominate and where political leaders were in denial for too long and blamed others for their own lack of planning. The current crop of male, authoritarian leaders, including Johnson and Trump initially frozen in denial, disregarded advice from practitioners because their followers were equally slow to appreciate the risk. Polly Toynbee was right to say that Johnson is the wrong leader for managing a pandemic when his lack of attention and early denial led to hundreds of NHS and social staff dying because of too little testing and poor protective clothing.

After the virus has moved on, the challenges of the climate emergency and escalating inequalities will demand much of political leaders. The public need to ask do they want leaders who lie and bluster or those who can both manage crises and transform economies?

Progressive leadership provides hope and currently it is being demonstrated internationally by some impressive women. It’s a no brainer.

Lauren Roberts-Turner is an A level student and ChildFair State Inquiry Young Leader.

On Friday the 20th of April, the schools officially shut to the majority of students, now as they begin to reopen what was the lockdown like for young people? And how might young people fare better in the future as a result of these experiences?

As Covid-19 closed the door to conventional learning and rites of passage, it simultaneously opened young people up to a wealth of opportunities online. Social distancing measures have put a stop to all events both two doors down the road and hundred miles away. However, modern technology and the internet is making it possible for people of all ages to tour museums in London, livestream plays and join nationwide conversations about climate change. All from the comfort of their own home. This is especially impactful for young people who may, under normal circumstances, be excluded from such events by funds, family situation or access to transport. The universal confinement caused by Covid-19 is giving many young people a greater sense of independence and, with that, freedom.

The internet, as well as providing young people more (equal) opportunities, is also providing them with a platform to share their experiences and opinions. Placing them on an equal footing with those who may previously have dismissed them because of their age. I am currently thoroughly enjoying the weekly New Economic Foundation briefings, yet as a seventeen-year-old, I would have found it hard to attend a physical lecture and even harder to ask a question or share my views. The anonymity of online participation allows young people to attend virtual events that they may have felt too afraid to otherwise. It empowers them to ask questions and allows them to have their opinion valued on its individual merit, free of prejudice.

The equalising nature of online communication is giving young people, across the UK, the opportunity to shape the sort of future society they would like to live in. Let’s not waste this experience. Together, with young people, and for young people, we can shape a better society for all.

Loving and Living

Laura Parker was the National Organiser for Momentum and before that worked in the children rights sector.

We have been asked for hopeful insights, 500 words the limit.

Before, that may have felt like too few words to encompass all we knew – about childhood, nature, power, music, language, violence, loneliness, wine, family, football, death, class, literature, beauty, chocolate, poetry, sex, mythology, oppression, food, dance, religion…

Before, we thought we knew how much it mattered.

Now – as we start to understand there is no ‘after’, just a next – we know it matters most of all.

And we need only one word.

Love.

David Robinson leads the Relationships Project and runs the Covid-19 focused Relationships Observatory.

750,000 people have joined the NHS volunteering scheme. More than 250,000 have volunteered with local charities. 4300 brand new neighbourhood groups working with more than 3 million people.

And this is the tip of the iceberg. None of this includes all the people who are simply helping one another, way below the radar.

The Relationships Observatory has been gathering stories and insights since the start of the lockdown. This is typical of many: “I put a note through the door of a couple of my elderly neighbours offering to shop for them. One of them called me and said she was touched by the offer. …I felt a bit embarrassed that we had never spoken properly before. She said it reminded her of how people came together during the war”.

Mass re-neighbouring and all this practical busyness is a pragmatic response to the emergency. Some of it will fall away when the crisis passes but we won’t unknow our neighbours.

If we just attend to the activity on the surface, however, we will reduce our vision of the future to a bunch of projects. We need to also understand the undercurrents – the shifting behaviours and attitudes that could prefigure more profound change.

We see for example a recalibration of risk and trust. Neighbours shopping and lending money to people they hardly know, doing things that would never be allowed in a Volunteer Manual. Statutory services giving budgets and discretion to front line staff, foundations and local authorities making grants to voluntary bodies without stifling constrictions. If the trust is honoured and the outcome positive, we won’t unlearn the experience.

It will be one of many things we will have learned, very quickly at this time. Another is how to use technology to build and sustain a meaningful relationship. For many, the internet offered, at best, a cold web, a mechanism for affecting transactions rather than for enabling a warm web of “real” relationships. Over recent weeks organisations like The Cares Family and Camerados have been very imaginatively deploying basic apps and programmes to facilitate meaningful connection. Others like the Local Area Coordination Network have been teaching and supporting individuals to use the technology and groups like the thousands of new mutual aid groups have shown the extraordinary potential of a blended web, combining WhatsApp or Facebook facilitated connections with home visits. We will, individually and collectively, benefit from this fast, experiential learning, long beyond the crisis.

All over the UK, we are seeing that change which might have been thought impossible, or would at best take a very long time, isn’t beyond us or even very difficult – 90 per cent of rough sleepers, for instance, have been taken off the streets.

We are learning that we are better than we often tell ourselves we are.

Post-Covid-19, we can be better still.

Hugo Dixon is a campaigner, journalist and entrepreneur

The pandemic is encouraging us to think about what really matters in life. Whom and what do we care for? What do we look forward to when the lockdown ends? What gives our lives meaning?

Quarantine may fill us with sadness and anxiety – and drive us crazy. But it also gives us time to think deeply. Some of this may stick when it’s over.

For many, a big part of what makes life meaningful is love, family and friendship. The crisis is bringing this into sharper relief. Sometimes we can’t see our friends and family. We miss them. When the lockdown is over, we’ll want to hug them. Will it be safe to?

But even now, we may be thinking about how we can care for our loved ones. How we can understand them better, as we go through this time of trouble.

The lockdown is also a pressure cooker. Close proximity and/or fear may create tension in relationships. That can be bad. But it can also force us to confront difficult aspects of our relationships – and they may get deeper as a result.

As people think about what is meaningful for them, they talk to each other about it too. So, there are discussions about what really matters, a joint exploration of what is important in life – and those conversations themselves are meaningful.

Although caring for family and friends looms large in these discussions, there are other common themes. One is the need to show compassion for ourselves. We are fragile creatures. It is okay to care for ourselves.

Another common theme is the need for meaningful work. We want to contribute to wider society in some way or other. Some, notably health workers, are able to do this more than ever during the lockdown. But others are missing out on meaningful work – and yet others never had the chance for it.

In a good society, everybody would have the chance to lead a meaningful life. As we plan for life after the pandemic, let’s try to hold onto the thoughts we are having about what matters and turn them into action.

Robert Phillips is the Founding Partner art Jericho Chambers and author of Trust me, PR is Dead

Better understandings of “trust” may yet flow from this crisis. Those who continue to peddle long-held trust myths will be found out and held to account. These are the fairy-tale leaders who make promises they cannot keep and, as one academic describes it, live in “the la la land of constantly sunny uplands”. Of the many things we have learned recently, no such uplands exist; fake promises are exposed raw by real news.

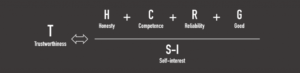

Two major shifts are coming. First, the shift from an abstract notion of “trust” (I trust him/ her/ them to do the right thing, whatever that actually means) to a more concrete understanding of trustworthiness. There is an equation to explain this: trustworthiness flows from honesty, competence, reliability and good. It is undermined by self-interest.

Reflect on this momentarily: those organisations and leaders who emerge from the tumult as saints will have demonstrated these characteristics. The sinners will be those who placed self-interest before the common good. Some have already exposed themselves.

The second shift is in the shape of trust. The 21st century has already seen movement here – from a vertical, imposed model (entirely top-down) to a peer-to-peer, networked one, where trust flows horizontally instead. It’s on this basis that we trust total strangers when jumping in their cars (Uber) or sleeping in their beds (AirBnB). Technology – and the traceability that it brings – is sometimes our friend.

The shift from the vertical to the horizontal model goes some way to explaining the marginalisation of experts, falsely captured within the 20th century understanding of institutional trust. They have had their time, so one argument runs – weakly, in truth, as it eschews the shameless politicisation of the anti-expert agenda. Now is most certainly the time to trust experts again.

Critically, a third dimension of trust is emerging from the crisis. We might call this “communitarian” trust – the wisdom of a community to act collectively in the best interests of fellow citizens, often hyper-locally. Hence the early decisions for lockdowns and safer social distancing measures, taken at a local level, well ahead of central government edicts; neighbourhood food suppliers figuring out delivery programmes for the vulnerable within an immediate locale; the return of neighbourly goodwill.

Adapt, Adapt, Adapt

Embracing and adapting to vulnerability

Anthony Painter is Chief Research and Impact Officer at the RSA.

Following Covid-19, the 2020s is about navigating vulnerability. Of course, vulnerability has always been with us but up until now it has been socially means-tested. If you are poor, a minority, or suffer from ‘vulnerable conditions’ you’ve always known what vulnerability is. Now, vulnerability is universal: experienced through threats to health, economic stress, and the experience of anxiety as we physically isolate and live with risks not just to ourselves but loved ones.

There are two natural responses: to turn in on ourselves or to have the courage to reach out in the hope that together we can create more resilient means of support. The first path involves seeing our parochial ‘herd’ as somehow detached from the rest of the globe and its biosphere. We would turn towards strong-men leaders who have all the answers even if they don’t have any solutions.

Rather than challenging our prejudices, our culture of nostalgia, our narratives of uniqueness and a notion of special status, we would become immersed in them. We would withdraw, unable to confront the collective psychological challenge of vulnerability. Looking back, we could seek to recapture an imagined past.

Another path is available: acceptance and adaptation. This requires the embrace of vulnerability rather than its denial. Brené Brown has articulated three components of healthy engagement with vulnerability: courage, compassion and connection. These elements are a good guide to the type of society we would want to see evolve.

Courage involves accepting that vulnerability is not reserved for the unfortunate few, it is part of all our lives. To respond requires universalist thinking to enable greater resilience to the shocks that are headed our way, not only pandemics, but climate emergency, economic shocks from the spread of new technology to brittle financial architecture, and geo-political shocks as great powers collide and new international configurations are formed.

People need to know they have an income when their vulnerability is exposed, and therefore Universal Basic Income is so important. They need to know that health, care and community services are there when needed and so capacity building here is critical. Good businesses need to know they can not only weather the storm but expand their capacity to innovate environmentally and socially as well as commercially; stronger financial systems of support will be necessary there. Community wealth building approaches have a strong contribution to make. This universalist approach to supporting people, new forms of productivity, and places requires a politics of reaching out, of compassion and bravery.

Ultimately, pandemics highlight that our fates are entwined, we are connected. The behavior of one, impacts the outcomes for all. A phoney individualism can hide this for a while, but reality always outs it in the end. Nowhere is this more pressing than in the context of climate emergency: we are within rather than masters of the planet’s ecology. Vulnerability requires progressives to tie together politics, power and policy in practical ways. In so doing, a politics of strong democracy opens out against a politics of the strong men.

Fernanda Balata is Senior Programme Manager for Environment & Green Transition at New Economics Foundation.

Covid-19 has undeniably given our planet some breathing space. With our economies – still heavily fuelled by carbon and environmental destruction – hitting the brake, we have seen significant impacts on the environment: a sharp decrease in global carbon emissions, lower levels of pollution and more wildlife sightings. But as we observe and reflect on those events, we must resist any narrative that tries to place a healthy planet against a thriving society.

We have already found a renewed sense of appreciation for those performing essential roles in society – our doctors, nurses, carers, farm workers, key services’ providers. This has made us question how we value different types of work in our economy and, I hope, means that we will lead the recovery by improving those workers’ rights, pay and conditions.

Each one of us now ponders on how much we are all connected and dependent on each other; let’s not leave the natural world out of it. Waterways full of fish, forests and woodlands rich with wildlife, fertile soil supporting a diversity of plants and fruits, an ocean beaming with jumping whales, sharks and sea stars; parks and beaches that boost our health and wellbeing, and walking in our towns and cities without needing to worry about the health risks of taking a deep breath!

These are not only the signs of a healthier planet; these are the very conditions that we need to thrive. Healthy ecosystems give us not only everything we need to live – such as food, renewable energy, clean air and raw materials – they are also what makes life worth living.

As we go through this crisis, and as we get out of it, my hope is that we truly connect with nature, and that the many benefits of a healthier environment are not only the privilege of a few but enjoyed by everyone. We need to go beyond superficial gestures or incremental measures to make this happen. We need to adequately value nature for all that it is and translate those values into our individual and collective choices and activities. We must transform our economic thinking and practice so that it is fit to deliver this vision.

We can do this. We can put all of the knowledge and experiences we already have into practice. We can shape a society where nature and people are not just allies so that we can thrive but become genuine friends.

People have an incredible ability to adapt, and nature has an incredible power of renewal. As we face the many losses and hardships this crisis has brought into our lives – but also celebrate hearing the birds singing, feeling more connected in our communities and learning how to use technology to maintain and build new relationships with each other – we should observe how nature rebuilds, never in exactly the same way, but always better. Nature learns and it transforms itself. That’s where we will find the inspiration and many of the solutions to build back better – not only our societies and economies, but also ourselves.

Layla Moran is the Liberal Democrat MP for Oxford West and Abingdon.

After times of crisis we often need progressive, forward-thinking solutions that revolutionise our country. I can only hope that once the coronavirus crisis ends, which it will, it marks a turning point for how our system works. That’s why I am flying the Liberal Democrats’ flag to implement a Universal Basic Income (UBI).

The coronavirus crisis has shown us that we are not all in this together. It’s the poor and the young who are being disproportionately hit by job losses. Meanwhile, it’s the very same group who make up many of our care workers, supermarket shelf stackers and transport workers. A UBI would first and foremost protect and benefit them.

In January, before we saw the very worst of Covid-19, I was calling for UBI pilots to be launched at a local level. More recently, I have worked with a cross-party group of MPs calling on the Chancellor to implement an Emergency Universal Basic Income.

My question to those who have the pessimistic outlook is clear: why would we not at least try it? Giving residents in our country a set income, that would act as a financial safeguard for millions, could be the catch-all safety net we are crying out for. It is the most efficient and compassionate way for a government to put the minds of the most vulnerable at rest instantly, forever easing anxiety for those who struggle to put food on the table.

Imagine this: the dust has settled on this crisis and the government decide to implement a regular, unconditional income to everyone in the UK, a hand up to the most hard-working and economically vulnerable in society. The prime example is low-paid workers, such as those in the gig economy. They often rely solely on their monthly wage; a UBI is their back-up provision should they suddenly not be able to work.

UBI is a message to all our citizens that says, loud and clear: we appreciate your hard work, we will help you and your family recover after this time of crisis.

The principle of a safety net to protect the most vulnerable is the very reason we have a welfare state, an NHS and a benefits system. Why now should we not be looking for the next big idea that can change millions of people’s lives instantly?

This could be a turning point in our country that sees a seismic shift in the way we deal with financial insecurity and poverty, particularly in-work poverty, forever – the government just need to listen.

I hope that we, in Parliament, can work together and mobilise across party lines. If we do and commit to radical, progressive politics that sets aside tribalism, we can change people’s lives for the better.

Frances Foley is Deputy Director of Compass, resident Events Organiser at Pembroke House in Walworth, drummer, runner, 5-a-sider and obsessed aunt

As boundaries between public and private have disintegrated, all our different identities have come into focus. In the crisis, we are parents, carers, friends, neighbours and everything in between. We’ve been forced to consider the varied, plural and interwoven strands of each individual’s life, which never starts and ends with their paid employment.

These multiple identities have suddenly become more visible, sometimes literally, as children bomb their parents’ TV interviews or someone’s untidy bedroom is revealed in a meeting. It’s harder to hide the personal. Such revelations complicate and confound the image we have of someone – but they are almost always humanising.

This sudden exposure is a kind of service that the virus is providing across society. As feminists have long argued, the personal is indeed political. It forms the bedrock of our politics, society and culture. But failing to acknowledge the intersection of these roles has exposed sharp inequalities, like the lack of care for children whose parents must go out to work.

For policymakers, individuals can no longer be easily instrumentalised; a person cannot simply cease to exist once they leave their place of work. This is both because for some the working sphere and the private sphere have become one. And for key workers, what they do when they leave really matters.

This should trigger a recalibration of how we see individuals, not just as units of economic productivity but as partakers in all the many strands it takes to sustain a good society. Each of us creates value in a multiplicity of ways and we must be freed up to take on as many of these as we can or want.

At a time of profound dislocation and alienation, the crisis has helped us realise the hitherto hidden skills of those we live alongside: the amateur baker, the bike mechanic, the community food grower, the circus performer cheering up local kids.

We instinctively understand that these roles are existentially important. They reinforce a sense of self and the opportunity to be different versions of ourselves. We may be feeling the loss of different roles by being confined to our homes and virtual meetings have only exacerbated this feeling: we use the same platform for all our relationships – work, family, romantic, social. It can be unsettling precisely because it underlines our need for multiple roles, for different ways of being us.

The community centre – a former settlement house – where I live, has always understood the potential of versatility. Residents, live-in volunteers with other formal jobs, contribute some of their time to the centre’s projects. ‘Try this on for size, it might fit you’, the opportunity says. So, we might cook a community lunch, organise street parties, write a neighbourhood newspaper, host poetry slams or teach singing to children. The value of versatility is demonstrated by the settlement motto: each has as much to gain as to give.

When we all return to work and slot back into former selves, we must bring those fuller selves with us to refresh our lives – and our politics. We all have hidden depths and talents. We need a society which gives us all more time to plumb them.

Sue Goss is a Compass Associate, gardener, public services change consultant and is the author of The Open Tribe

What matters now is resilience. This is not the last, or the worst, catastrophe we will face, given our short-sighted, reckless approach to our planet. Of course, we need a powerful state, able to marshal resources, legislate effectively and deliver solutions. We begin to see how leaving the EU makes us vulnerable without the muscle and power of a big economic bloc. We are sceptical about motives – and where the money will end up. We worry about the dangers of authoritarianism. State power, if it is to serve a democracy, has to be held lightly and transparently so we, the citizens, can see why and how it is acting. But if things are to change, the shift we need is greater – from public acceptance that society serves the economy, to a reality where the economy serves society. We need interventions that shift towards a self-balancing system, with dynamics that are redistributive and sustaining.

Centralised, highly specialised systems are efficient in periods of stability, but fragile, clumsy and ineffective in situations like this. We are watching layers of bureaucracy and control slow down every initiative – from recruiting volunteers to buying PPE. Resilient systems have high levels of diversity and redundancy – with multiple alternative options – faster, cheaper and more creative. When many people are finding solutions, not all the solutions have to work. More distributed systems would involve radical decentralisation not simply to local authorities, but to regional partnerships, local partnerships and to community coalitions.

We in Compass have often talked about moving from ‘control’ to ‘empowerment’, but in reality, governments are useless at empowering people. ‘45 Degree Politics’ describes our work to build the capacity of government, local and central, to work with communities, not strangle them with bureaucracy. But in civil society, things don’t always go right. The most vulnerable are powerless. Communities lack resources. There is no single ‘community’, but multiple interests and identities. Community is a construct, and while it can be constructed as open and creative; it can equally become closed, aggressive and hostile to outsiders.

We are learning a language of eco-systems – moving from, as Kate Raworth says in Doughnut Economics, ‘machine brain’ to ‘garden brain’. Can we begin to see a state role as to ‘tend’? Creating the conditions for collaborative decision-making; redistributing resources; controlling and regulating greed; ensuring levels of public education that make informed discussion possible; and setting rules of behaviour in the public realm that create solidarity, tolerance and generosity. To push the gardening metaphor – one of the things that gardeners do is to protect diversity – to tackle the thuggish weeds that threaten to create a monoculture, to protect the most vulnerable plants and to create a deep rich soil in which all sorts of organisms flourish.

When we emerge from the pandemic, could a citizens’ assembly discuss not only the scale of government and the policies it should implement – but a change of capability and role? Can we start to think about a resilient democracy, one that designs in distributed power, transparency, and a permanent conversation between government and governed?

Tom Schuller is former Dean of Lifelong Learning at Birkbeck. Author of Learning Through Life (with David Watson), and The Paula Principle: how women lose out at work and what to do about it.

We’re all having to learn a lot of new stuff: about disease, about our neighbours and about ourselves. Humans are natural learners, and now is the time to give that natural propensity a proper and positive outlet. We can achieve that by doing four things:

- Rebalancing our education system so that it offers earning opportunities across the full lifespan;

- Building on the extraordinary access that digital technology gives us – or most of us – to information and to each other’s knowledge;

- Changing the culture at work so that learning becomes a natural part of any employment contract;

- Thinking of learning as something we do together as well as individually.

The Covid-19 crisis is generating new initiatives and interdependences. My local Mutual Aid group is asking “Could you do a beginners language session, a music class, teach others to draw or something similar? We would love to help you share your skill with the community.” I’m sure similar ideas are popping up all over; the challenge will be to sustain them.

We have the tradition and the experience to draw on; what we need is the imagination to conceive of how things could be different, and the determination to overcome vested interests. The 19th century saw a flourishing of institutions and ideas promoting learning for all, with the foundation of the Mechanics Institutes, the Workers Education Association, university extramural provision and libraries of all kinds and many others. The 20th century saw community education, the Open University and the rise of professional and vocational training. The last 10 years, sadly, have seen a serious shrinking of provision for adults in almost every respect. We can turn that around.

The first paragraph gave 4 broad areas where fresh ideas are needed. These can be local or national – one of the great things about learning is that it cannot be squashed into a single frame or format. Anyone can innovate, and we now have the means to let others know very quickly about successful innovation. Here are three specific proposals:

- Design age/stage-related educational entitlements, for example: (a) Give every 18 year old access to support for a certain amount of free education, say two years, to be taken any time before age 30 (b) At the other end, attach to the first pension payment a voucher for education and the offer of an educational guidance session.

- Develop models for educational leave in the same way as we think about holidays or parental leave – a natural part of any employment contract.

- Introduce Mutual Learning Exchanges: digital but also physical spaces where people of all ages can teach and learn from each other, across generations, pooling experience and sharing what they are gleaning from digital technology. Physical space for MLEs (Maximum Learning Experience) to be established wherever appropriate – colleges, schools, libraries but also shopping malls, sports arenas, cafes.

Solidarity

Ruth Lister is Chair of the Compass Board, a Labour Peer and Emeritus Professor of Social Policy at Loughborough University.

Worsening poverty statistics and the material impact of Covid-19 notwithstanding, the wider ramifications of the latter do give cause for hope as the realities of poverty are brought home to more of us. In the early days of the crisis, it was striking the number of commentators who expressed incredulity at the low rate of statutory sick pay (now £95.85 a week), apparently oblivious to those who already had to live on even lower social security benefits. Although the adult standard universal credit allowance rate has been increased temporarily to match SSP, other elements and the legacy benefits universal credit replaced remain untouched. Many people will be learning for the first time just how low social security is and will be experiencing the problems associated with claiming universal credit.

Given dominant political and media discourses about claimants ‘languishing’ on generous ‘welfare’, this could come as something of a shock and could colour their future attitudes to the social security system. The case for a social security system that provides genuine security through comprehensive protection at levels sufficient to allow life in dignity, reflecting human rights principles might, in future, fall on more receptive ears.

More fundamentally, as many more people are swept into poverty as a result of a shock outside their control, misleading individualistic explanations of poverty that attribute its causes to the behaviour or capacities of people in poverty themselves could lose their purchase. In the same way, it will become harder to divide the population into ‘hard-working’, self-reliant families and the ‘dependent’ workless. Many more people will now understand how easy it is to fall into poverty through no fault of their own and will experience the insecurity of hovering just above the poverty line or of cycling in and out of poverty. A shared experience of economic insecurity could potentially provide a common platform for future anti-poverty action to prevent as well as mitigate poverty.

The pandemic has also shone a spotlight on the low value attached to the work of carers and other low paid workers previously dismissed as ‘low-skilled’ (including many first and second generation immigrants) who have now emerged as ‘key workers’ vital to the maintenance of society. The case for improving the rewards for such work, argued by feminists among others for years, has now become overwhelmingly obvious.

Although claims that we are all in this crisis together are demonstrably false, not least as those on low incomes and BAME groups have suffered disproportionately, it is also true that people’s reactions to it have brought many of us together. As Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett observe, this makes us ‘feel we have more in common’. That makes it harder to continue othering and dehumanising people in poverty. As does the emergence of networks of people with experience of poverty who are speaking out as ‘experts by experience’. The more their voices are heard the greater the hope for the future.

Zoe Gardner is a migrant’s rights campaigner and Policy Advisor at the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants. Recent articles about migration policy in the time of coronavirus on Politics.co.uk and Free Movement blog.

This situation may be unprecedented, but in some ways, we have been here before. Every time our society faces horrifying and unpredicted events, it is always the same people most impacted by the crisis. Finally, during this pandemic, the understanding of how much we all depend on one-another and how none of us are safer than the most vulnerable among us is breaking through – permanent, systemic change is the only way forwards.

Migrants, especially those with insecure or no legal status in the country, are those facing some of the worst risks to their health and their livelihoods as, through the government’s Hostile Environment, they are criminalized for working but forced to remain in work to avoid destitution. They are denied access to housing and healthcare and are constantly at risk of the brutality of immigration enforcement, detention and deportation.

When a very different kind of disaster happened, the Grenfell fire, residents who were undocumented were similarly at most risk – our government’s hostile approach to migrants meant they were unable to access relief and support, once again at the sharp end of the crisis. However, the response from the Government, although lauded at the time, proved to have only been a sticking plaster rather than the systemic change that was needed. A limited amnesty for undocumented people, introduced in response to public outcry, expired after 12 months – leaving them once again subject to the Hostile Environment. Now, just as then, as the public start to take note of the people providing us with food, cleaning our hospital wards and caring for our family members, it is vital that we ensure that we call for changes which will be cemented permanently into our immigration system.

Already the pressure is on – the government has had to delay its Immigration Bill, afraid of the political embarrassment of introducing yet more restrictions at a time when even the likes of Piers Morgan is having none of it. Now is the time to push them to concede the hostile ground they have occupied at migrants’ expense for so long.

The government’s Hostile Environment must not survive this crisis. Measures that have made our whole society more vulnerable to a deadly virus must be scrapped at once. The resources wasted chasing down the migrants who are keeping our society going must be redirected to community support and development projects. The cruelty and stupidity of NRPF visa conditions has been comprehensively exposed at a time where so many more of us have come to understand that sometimes, we must all rely on a state security net. The madness of charging migrants for healthcare and making the NHS unsafe to access because of sharing data with immigration enforcement has been laid bare – our public health protection is only real if it is truly universal, a value our country holds dear and will not allow to fail again.

People lose their immigration status for all sorts of reasons, family break down, mental break down and inability to pay extortionate Home Office fees among them. While our system remains cruel and inflexible it continually produces people without status. This must never mean destitution or a death sentence again. The urgent suspension of the Hostile Environment in the face of this crisis must not be just a sticking plaster: new, accessible, affordable and flexible routes to regularisation will be a key part of the new deal for migrants that we need.

*Updated (15/05/2020): The Immigration Bill is returning to the House of Commons on Monday 18th May.

Isaac Stanley is a Senior Researcher at the Centre for Local Economic Strategies (CLES) and a Compass Associate. His recent writings include Love’s labours found: Industrial strategy for social care and the everyday economy.

Our economy works by denying a double dependence: on the natural environment, and on the caring and nurturing work that sustains our existence (what feminist economists have called ‘reproductive labour’).

Climate activists have successfully forced dependence on the natural environment into the public consciousness. The need to respect our planet has moved from a fringe concern to a ‘doorstep’ issue, that politicians in countries like the UK cannot afford to ignore.

It is possible to imagine how the Covid-19 could be the beginning of a comparable shift in the politics of reproductive labour. The pandemic has provoked a rare outbreak of recognition for the “keyworkers.” It has become impossible to ignore the essential nature of the work performed by care workers, supermarket workers and cleaners – in contrast to much higher-paid work of ‘high-skilled’ white collar workers, many of whom find themselves ‘furloughed’ or working from home. Lockdown has exposed the inadequacy of the conception of value which underpins our current economic order.

It is not a given that this epiphany will deepen or endure. Ministers insist that “now is not the time” to discuss improvements in keyworkers’ pay. The dominant idiom in which their contribution is evoked is sacrifice; and, exposed on the front line with inadequate personal protective equipment, they are in some senses more devalued than ever. Nevertheless, the reasons to hope are significant, and the conceivable shifts profound. What kinds of changes could this mean in practice?

Take adult social care work – perhaps the most striking example of undervalued reproductive labour. Simply pumping more money into the current system would not result in improved pay or conditions, as provision is currently dominated by extractive chains which divert resources away from the front line. Nor would increasing entitlements do anything to improve the narrow prevailing model of care, as a series of 15-minute slots focused on bio-maintenance tasks – clearly inadequate in meeting the wider human needs of care receivers.

Beyond increasing funding and entitlements, then, a post Covid-19 society would need to invest in more radical experimentation with the form of care it provides. Social care would to be treated as a priority area for ‘industrial strategy’ investment, just as important as the high-tech sectors currently prioritised. This industrial strategy would not blindly pursue productivity, but would focus on the substantive task of developing and embedding new, better service and business models required to secure the wellbeing and dignity of both care givers and care receivers.

New models of care would give care workers greater opportunities to apply their imagination and creativity, and co-design services with care recipients. They would be associated with more varied and fulfilling roles for care workers, clearer pathways to progression, and improved access to life-long learning. New business and ownership models such as platform cooperatives could restore agency to care givers and receivers, as well as raising salaries. New forms of commissioning would nurture and embed these models, while new forms of regulation better reflecting the true value of care work would ensure that innovation was steered in a healthy direction.

This is what it would take to truly recognise the value of reproductive labour. In a society willing to make these collective investments, those who had previously been indifferent would have the chance to rediscover the humanity of the ‘keyworkers’ – and, in the process, to rediscover their own.

The Rehabilitation of Universalism?

Francesca Klug is a Human Rights academic and advocate

The Doomsday Clock has been at a 100 seconds to midnight for a while, but only now do we hear it ticking.

In this global pandemic we face a common threat that none of us have experienced in living memory. Instead of a war which divides nations into allies and foes, we all face the same biological menace. We may be alone in our multiple self-isolations, but we recognise ourselves in each others’ reflections – in the anxieties, frustrations and hopes etched on the features of human beings everywhere.

America is now first, solely in the sense of having the highest number of Covid-19 infections and deaths in the world. The security of its citizens, of all citizens worldwide, cannot be guaranteed by building walls or a new generation of nuclear weapons. An outbreak anywhere can become a threat everywhere. A vaccination or treatment accessible to all nations is what will end this crisis. ‘Vaccine nationalism’ is now recognised as the most immediate threat to humankind. Competition will kill us. As with our climate emergency, multilateral co-operation, global institutions and universal standards are our only routes to recovery.

Here in the UK, Covid-19, like dye in a vein, has illuminated disparities in class, ethnicity and health more vividly than any policy papers or committee enquiries. The lid has been lifted on structural inequalities which literally impact on life chances. But these differences have only reinforced our sense of inter-connectedness. Where would any of us be without someone willing to risk their lives, use their skills, apply their learning and dispense their empathy to support us? Indignation over inadequate protection or poor pay for nurses, doctors, carers, porters and cleaners has become a shared preoccupation. Neither celebrities nor hedge fund managers can keep us safe or supply our basic needs.

Only now, after years of austerity when some of the poorest and most precarious took the biggest hit, whilst the richest were protected, is it possible to imagine a national debate on a universal basic income replacing a tabloid obsession with so-called scroungers and shirkers.

Only now, after generations of stigmatising migrants and asylum seekers, can we conceive of replacing a hostile environment with a welcoming one.

Only now, as health workers from overseas die trying to save us, are we shocked they are surcharged for using the very health service they maintain.

Following an era when the steady drum beat of slurs against ‘citizens of nowhere,’ ‘cosmopolitans’ and supposed ‘globalists’ grew ever louder, might the benefits of a universal ethic once again receive a hearing? After the last major global catastrophe, the world adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Over 70 years later our interdependence has never been starker. As we face growing global threats to our planet and our health, the realisation that we are “all members of the human family,” as the Universal Declaration proclaimed, might be all that stands between our future and that doomsday clock.

Sue Tibballs is Chief Executive of the Sheila McKechnie Foundation

The social sector in this country – all the myriad organisations that exist primarily for social good, from charities and community groups to social enterprises, faith groups and trades unions – could play an absolutely central role in harnessing the positives from Covid-19. This is what I think the sector needs to do to capitalise on the opportunity.

- Remember that this is a sector of social reform as well as aid. Recent decades have seen this sector slide inexorably into an increasingly marketised and apolitical model in which the idea of charity – understood as attending to immediate need – is comfortable, while the idea of reform – challenging the systems that create those needs – is not. We have become stuck in transaction, not transformation. As long as we are there, we cannot play our full role or realise our full power. We need to tell ourselves and others a new and more powerful story about who we are, what makes us unique and valuable, and the capacity we hold to drive transformational change. What we at the Sheila McKechnie Foundation have dubbed ‘Social Power’.

- Be more porous to wider civil society. Covid-19 has inspired an upsurge in civic action and concern, from the rapidly organised Mutual Aid WhatsApp groups to clapping for the NHS and frontline workers. More widely, we have seen the emergence of a whole new wave of citizen-led movements from #metoo to Extinction Rebellion. In order to harness and build on this energy, the formal (legally constituted) sector has got to become much more porous, finding ways to plug into and support these more organic movements in a mutually beneficial way. This is happening at the margins. It has to hit the mainstream.

- Don’t be afraid to be political. Recent administrations have done a good job persuading the social sector that it doesn’t belong in politics. It does. Because politics is, of course, for everyone. The current shift in public attitudes driven by this extraordinary experience will not automatically convert into pressure for progressive change. But the social sector can help with this. We can create spaces, invite discussion and help bring people in.

- Linked to this, we need to inspire and mobilise our significant audience – from members and donors to volunteers and staff. This sector may not be big in terms of turnover – but it is huge in terms of reach. Way beyond that of the political parties. The relationships the sector hold are often powerful because they are built around shared values and a common desire for a safer, fairer, more sustainable world. Our currency is passion. And passion is powerful.

- Work together more and speak with one voice. Organisations in the social sector are incentivised to compete. So, this is hard. But we have got to work together where we have common cause.

- Set an agenda to Government. Don’t just petition. My sector has become accustomed to asking governments to make change rather than using its power to command change. Much significant social change through time, originated in civil society – from Universal Suffrage to the Living Wage – but we seem to have forgotten that. We need to take our place at the table alongside the public and private sectors, and use the full force of our passion, our experience, our audience and the incredible energy out there to assert what we want to happen.

This government knows that it is going to be relying more and more on the social sector in the years ahead as the pressure on the state increases. This is a time to insist on a new contract, just as Beveridge did after the War. This time, it has to be on the basis that you can’t have the benefit of our charity without the full power of our belief in reform.

Danny Sriskandarajah is the chief executive of Oxfam GB

The clap for carers phenomenon has been one of the most heart-warming aspects of lockdown. Yet, while the applause is genuine, albeit overdue, it is out of sync with the woefully inadequate economic recognition afforded to those who look after others. Whether working for meagre wages on insecure contracts in care homes and nurseries, or caring at home for family members, it’s a shocking fact that carers in Britain are significantly more likely to be in poverty than those without caring responsibilities.

But with the formerly invisible army of carers now firmly on the nation’s radar, this could be the moment they finally get the pay rise and protection they deserve. In May, more than 100 organisations including Oxfam, Carers UK and the Women’s Budget Group united to urge government to act to protect carers from poverty. There is strong public support for a better deal for carers – a recent YouGov poll found 78 per cent of people in the UK think care work is not valued highly enough by the Government and 70 per cent think care workers are paid too little.

Before this crisis hit, too many carers were living below the breadline, struggling to stay afloat. The pandemic has made a grim situation worse, not only putting carers under significant strain, but in many cases hitting household budgets due to loss of income and increased expenses. Katy Styles, whose husband has a degenerative disease, said: “Besides the financial implications of the crisis, physically I’m exhausted and mentally I’m crushed. And yet through Carer’s Allowance, the government values my efforts at less than £10 a day. It makes you feel worthless.”

This is a once-in-a-generation opportunity to overhaul the care system. There are simple, practical steps the government could take now: increases to social security levels, increases to key benefits including Carer’s Allowance and Child Benefit, a significant cash injection into the underfunded social care system, and acting to ensure that social and childcare providers pay their workers at least the Real Living Wage.

But this is about more than money, it’s also a chance to transform attitudes. The vast majority of carers are women, which reinforces gender inequalities, especially when combined with discrimination based on age, disability and race. Worldwide, women and girls put in 12.5 billion hours of unpaid care work daily, equivalent to an annual contribution to the global economy of $10.8 trillion – more than three times the size of the global tech industry. Countless more are paid poverty wages for care work.

Let’s radically rethink how we value care and stop taking carers for granted. Let’s invest more in care and other public services that make life easier for those with care responsibilities, and break down barriers holding back women. Let’s give carers the respect and support that they give to others. Now that would be truly something to applaud.

Business as Usual?

Loughlin Hickey is a founding trustee of, and senior adviser to, A Blueprint for Better Business.

How refreshing it is to see when the shackles are off, we become human again; a little bit selfish and fearful maybe but also looking for something useful to do, in solidarity with our community, treasuring precious relationships. And the artificial barriers between business and community torn down shows we can be human in all we pursue, including in business. The true purpose of the best businesses coming through as a beacon of hope for a better future beyond the crisis. We can now see how business can be a force for good as part of society, and not apart from society and the pursuit of profits being a sufficient contribution. We can now see business for what it truly can be – not a series of anonymous contracts enforced by the powerful but a series of relationships in service of people and society.

And government and business working in harmony to recognise the social as well as the economic aspect of business, not least through the desire to maintain as many jobs as possible in the realisation that jobs are both social and economic bonds. And using the banking system to deliver government support for business, and collaboration to adapt policies to achieve the objectives, rather than remain hampered by unintended consequences of hastily assembled support programmes.

Businesses adapting to remote working for the safety of their people rather than chafing against this freedom to work away from supervision and a manager’s gaze. Using technology to check in on a teams’ well-being rather than simply their productivity. And for those in the front-line, outside of healthcare, trying to adapt the ways of working to protect both staff and customers and prioritising those in need, as people come before profits. Adapting their productive capacity and ingenuity to contribute directly to the needs of society, not least for sorely needed healthcare products and indeed new hospital capacity. And thoughtful decisions not to participate in government financial support if other resources were available (including preserving resources through cancelled dividends and senior leadership pay) – so that the support remained available where it was most needed.

The true purpose of business is now emerging rather than statements of purpose; financial support for and donations of goods and services to those societal organisations who are best equipped to get help to those most in need, support for the well-being of colleagues and trust in their ability to contribute with support rather than supervision, empathetic leadership, partnering with government, adapting capabilities to contribute to a common good. What a future that could help usher in.

Christian Wolmar has been writing on transport matters for 25 years and was formerly transport correspondent of the Independent. His latest book is Railways.

The first time I saw a father cycling with his two very young children in the road past my house the other day, it almost brought tears to my eyes. This is precisely the dream that I have been fighting for in many years of writing and campaigning on transport. And now, in the horrible reality of our Covid-19 world, it has become commonplace.

But why should it be in exceptional circumstances only that our roads can be safely negotiated by the most vulnerable in society? The crisis has illustrated that a far better way of using our streets is not just desirable but possible. While some of the traffic will inevitably return, why not use the opportunity to ensure that it will still be possible for kids to use the roads, by simply ruling that all residential streets have a speed limit of 15 or even 10 mph? And then go a small step further by stipulating that cyclists and walkers have priority when crossing or using these roads. In the Netherlands streets like this are called Woonerf and are the norm in many towns.

It has been noticeable that the few remaining drivers on our streets have shown a conspicuous new level of consideration towards these novice cyclists, reducing their speed and giving them and their escorting parents a wide berth. Why cannot this become the new normal? Why don’t we stop listening to the arguments perpetrated by a minority of boy racers about the iniquities of speed cameras and speed bumps? Instead, roads can become streets once again, not thoroughfares which impoverish rather than enrich the local environment. The number of children I have seen cycling in London these past few weeks shows there is considerable appetite for this form of transport and exercise, which up till now has been stymied by fear. What sort of a world have we created in which our children cannot safely use our streets?

As for the main roads, look at what is happening in Milan and Paris. In order to entrench some of the positive effects arising from this terrible pandemic, extensive new networks of cycle routes are being built. And just as importantly, the countries’ leading politicians are talking about how cities will now have to change. We need that kind of leadership here – in London, Manchester, Birmingham, Liverpool, Leeds and other countless smaller towns and cities.

Bringing about such a change would also have another positive effect. The reduction in traffic since the lockdown has resulted in a radical improvement in air quality. The relationship between car use and pollution can no longer be disputed. Moreover, there is a clear link here between health and transport. Most of the people dying from Covid-19 have had underlying health conditions, many of which, like COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease) and asthma, are particularly prevalent among those living on busy roads. Improving local air quality is therefore an essential prerequisite to reducing people’s vulnerability to more lethal viruses in the future.

There is another reason why we should focus on cycling and walking. For a time after this crisis, many people will be reluctant to use public transport, given the difficulties of social distancing. The bicycle might be their only alternative to using the car. Cycling, therefore, should not be seen as a ‘nice to have’ add-on but as an essential part of transport policy in our new post-Covid-19 world. In the way that Joe Wicks may have inspired primary schools all over the country to have 30 minutes’ PE at the beginning of every day, let’s use the bicycle, arguably the greatest invention the world has ever seen, to help solve the crisis of extreme health inequality that has been cruelly exposed by this terrible turn of events.

Work, Fulfilment and Obligation

Shuvo Loha is a Compass Associate and Co-Chair of the Compass Council.

In crisis we find we are suddenly more appreciative of the work other people are doing for society.

But whilst we applaud, we must expose the myths of free-market orthodoxy that says people get paid what they are “worth” and that market forces magically optimise pay via supply and demand.

Pay for essential workers like nurses, supermarket staff and factory workers have not followed capitalist textbooks – that insist that since demand for their services have increased exponentially, so should their wages. But this is what the existing economic models predict.

In place of this free market failure, we must build new institutions to make sure wages are in line with the true value people bring to society and to ensure continued recognition of the jobs they do. We need policies that treat work not just as a means for income and production but also as an expression of our own fulfilment and our obligation to society. We need economic models that can deal with the complexity of real life and compute widgets differently to human beings.

As far as being human is concerned changes in work patterns have opened a window into what it means to actually “put people before profit”. Whilst the crisis has brought out the worst in some, it’s brought out the best in many. Employers put employee welfare ahead of sales, businesses sought to protect their customers before profit. We showed each other more of ourselves as housemates appeared in the background in work Zoom meetings, as deadlines were missed because we had to school our children at home. There is at this moment a general feeling of greater empathy which we must seek to grow as the crisis itself subsides. At work we’ve been forced to reckon with multiple strands of a person’s life, not just the professional. It is this expression of our whole humanity in which lie the seeds of destruction of the commodification of human labour at the heart of modern capitalism, which has no place for ethics, sees people only as a means to an economic end and is thereby completely estranged from the reality of humans as social beings first and foremost.

The commodification of labour has become so normal that the daily commute for many (in the biggest cities at least) is one which wouldn’t even be appropriate for cattle herding to the abattoir. So normal, that instead of meaningful work and a meaningful place in society we get zero-hour contracts and the legitimisation of insecurity that means giraffes in the London Zoo have greater certainty over essentials than some of our fellow citizens. So normal, that we accepted this grotesque status quo as our inheritance and embraced the ideology of market power as our bible.

The new normal must be to aggressively assert our humanity at all times and demand the same from our colleagues, our policy makers and our politics. Only then can we build an economy that society needs rather than accept a society that we’re told the economy needs. We can and must #BuildBackBetter.

A better way of farming and shopping

Martin Yarnit is a Churchill Fellow. You can read his report on US food hubs and Italian coops here

A dangerous reliance on processed and imported food, factory farming, imported labour to harvest fruit and vegetables and the monopoly power of the supermarkets – Covid-19 has brought into dramatic relief things we’ve known about for years. But the crisis has also given a boost to local producers and suppliers. Doorstep milk deliveries, veggie boxes and home grocery deliveries have all flourished aided by the disruptive power of the internet.

A new sustainable way of farming and shopping is beginning to take shape. A key feature of these new developments is something the Rochdale pioneers would have appreciated: a partnership between producers and consumers to deliver better returns to small farmers – long used to being squeezed, almost to death, by Tesco and the others – and better quality food – but not at the expense of the land.

We should build on nascent local initiatives such as Bridport-based Local Food Links. Founded in 2007, this community interest company (CIC) uses four kitchens to cook and supply school meals using local produce (‘whenever we can’) to more than 50 schools, primarily in Dorset. Another example of the new way of doing food is Kent Food Hub whose aim is to create an online marketplace for locally produced food to reach people across the county. The UK has a growing but still small cooperative sector. The Tamar Valley Food Hub, in the South West, which brings together more than 50 producers in an online marketplace, passes on more than 85 per cent of the retail price of produce to the producers.

All this is a portent of what the future may hold for us in the UK, but it is still low key and small scale. To grasp the potential for new cooperative ventures in food we need to look abroad. France has a consumer brand owned by a cooperative of 7500 members set up originally to protect the livelihoods of dairy farmers. French consumers have bought 123m litres of milk labelled C’est qui le patron?! (CQLP -Who’s the boss?) since its launch in November 2016, making it the fourth-biggest milk brand in France, outsold only by the most cut-price supermarket-own brands.

In the US, more than 200 food hubs have been set up with federal support uniting the interests of producers and consumers. Last June, I went to visit The Redd, in Portland (OR), a purpose built, state of the art facility, initiated by a trust with federal funding. With more than 20,000 square feet of warehouse space, the Redd provides cold storage, aggregation, packaging, and distribution services in partnership with B-Line Sustainable Urban Delivery. It also provides space for incubation. Through the Redd, rural producers can make one efficient drop rather than dozens all over town. The US is a hotbed of food experimentation. Chicago’s Food Policy Action Council has persuaded the city council to use its public procurement power – its annual spend is $325m. – to promote a race to the top on health, working conditions, animal welfare and nutrition.

Building on the best practice at home and abroad requires a recognition that food and farming is a legitimate interest of the state, coupled with investment in local infrastructure – hubs and coops – and internet-aided distribution. The monopoly power of the supermarkets and factory farming can be broken. Above all, for the sake of our security as a nation, we have to boost the supply of home-produced food. We did it before – during World War Two – and we can do it again if that’s what we demand.

Public health before private wealth

Fran Boait is Executive Director of Positive Money

As the government tries to return to ‘business as usual’ central to the conversation is the familiar phrase ‘we must get the economy growing again’. But critiques of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as a measure of economic progress are widespread. The global pursuit of GDP growth has repeatedly failed to enhance life satisfaction, alleviate poverty, or protect the environment.

With the economic rulebook of the last 40 years seemingly ripped up and out the window since mid-March, now is the time to ask the big questions such as: what is the point of our economy if not to help us build a good society? Why would we try and restart an economic model that is failing people on so many fronts?

Perhaps reimagining our priorities as individuals, as communities, and as a society is exactly what we need to build hope. We intuitively know that our economy doesn’t work for us, and our recent polling backs this up. Right now 8 out of 10 want the government to put health and wellbeing above economic growth, and 6 out of 10 want social and environmental indicators to be more important than economic growth for assessing policies after the pandemic is over.

In our recent report The Tragedy of Growth we outline that the absence of growth in capitalist economies generates strong tendencies toward unemployment and deepening inequality. So, there are some big barriers to throwing away GDP growth completely. We can however facilitate our escape from the growth paradigm through a range of policies, many which have gained huge support through the economic fallout of the pandemic. These include monetary financing, a universal basic income ideally issued via central bank digital currency, a direct clearing facility, public banks and modern debt jubilees.

To protect human wellbeing and avoid environmental disaster, we must escape the growth paradigm once and for all. Right now, the UK government should join the ‘Wellbeing Economy governments’ alliance, Scotland and Wales have already done so. The ONS should stop the publication of GDP figures (and thus end the media frenzy) and focus entirely on its ‘Measuring National Wellbeing Programme’, which includes a dashboard of alternative indicators, such as life expectancy, unemployment rate, job satisfaction, access to key services, and greenhouse gas emissions. In turn, instead of targeting GDP growth, the Treasury should focus on achieving better social and environmental outcomes directly, incorporating the wellbeing dashboard into its budgeting process, as New Zealand has already started doing.