Mark E Thomas of the 99% Organisation on how a Progressive Alliance can seize the narrative back from the hard right.

In the UK, we have a government whose former colleagues describe it as ‘extreme right-wing’; which has handled the Covid-19 pandemic to produce the third-worst death toll in the world; and which has also produced one of the worst economic performances. That performance is further weakened by the government’s hard Brexit, which is dramatically reducing the UK’s ability to export to the EU.

You might expect that in response to this, progressive parties would be riding high in opinion polls.

However, if there were an election tomorrow, recent polls predict the Conservative party would win again.

How can this be?

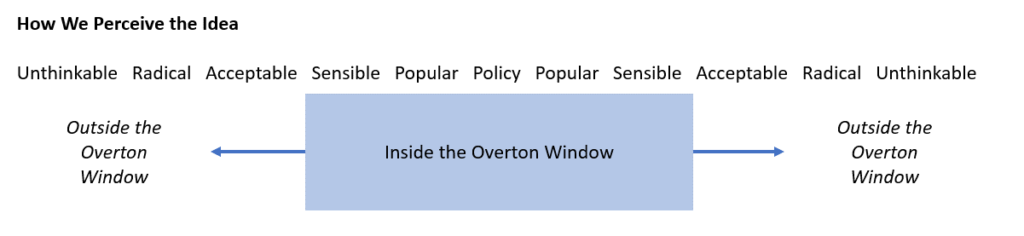

In politics, some things are acceptable and some aren’t. But which things are acceptable and which aren’t is not fixed over time: some ideas which would have been too outlandish 100 years ago are now generally accepted and have passed into law – gay marriage, for example – and other things, commonplace a few decades ago, are now illegal, such as smoking on aeroplanes or in pubs.

The ‘Overton window’ describes the range of policies which can be discussed and possibly acted upon by politicians. It illustrates how some ideas may be perceived as too extreme left and others as too far right while others are perceived as mainstream.

Politicians can ‘safely’ campaign inside the window; if they stray outside, they risk being perceived as dangerous extremists and becoming unelectable. It is others who can safely move the window.

In order to move the Overton window and enable progressive policymaking in the UK, we need an alliance between and a change in strategy on the part of opposition parties and a range of other progressive organisations.

What happened to the window?

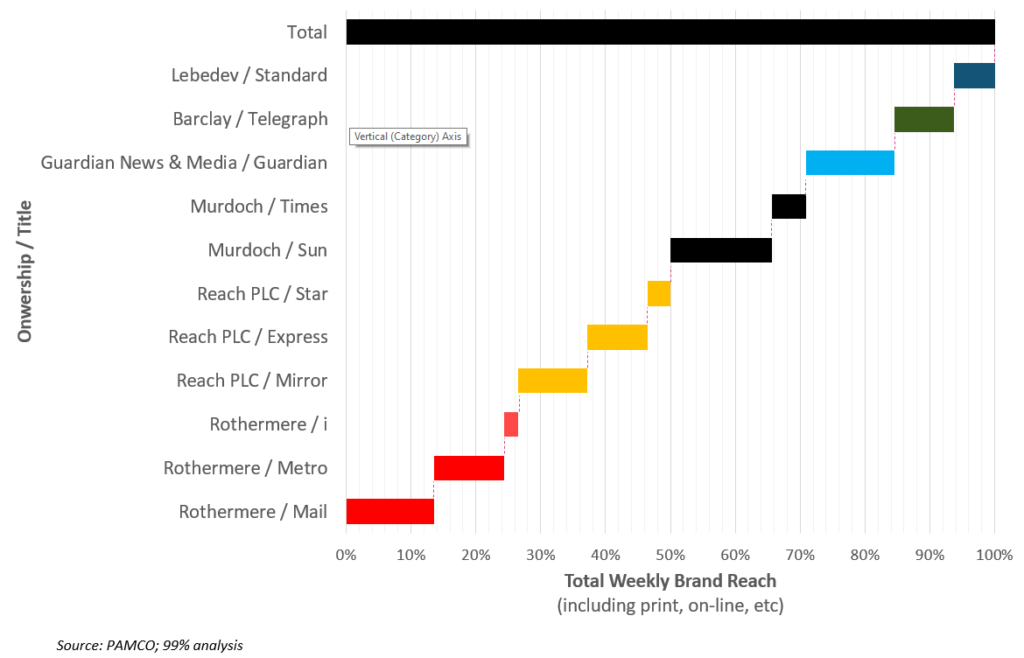

Over 80% of the UK’s mainstream media is owned by four billionaires whose wealth is kept offshore so as to avoid taxes and whose interests are unconnected with those of British people.

These media largely determine what the British population knows about its government, and sometimes they can create a very misleading impression.

For example, let’s compare US and UK media coverage of the same issue.

When the US passed 100,000 Covid deaths, the New York Times highlighted the scale of the death toll and the fact that these were individual lives, not just statistics.

Our newspapers, in contrast, marked the passing of 100,000 deaths not by emphasising the scale of the catastrophe or with searching questions, but with pictures of the prime minister and coverage of how sorry he felt for the victims.

The image presented was of a caring, hard-working statesman, weighed down with unbearable responsibility in the face of an intractable problem – as if Johnson were the victim rather than the person with ultimate responsibility for managing this catastrophe. The Daily Telegraph headline read: ‘I am deeply sorry for every life that has been lost.’

Other stories are barely mentioned. The British Medical Journal, the official journal of the British Medical Association, condemned the UK government’s (and others’) handling of the pandemic. They described the badly performing countries as having committed ‘social murder’ and called for an urgent public enquiry.

While you might expect such a strongly worded statement to be widely reported, so far the Guardian is the only national newspaper to have covered it.

The opposition parties’ narratives face issues, as traditional media have shifted the Overton window so far to the right that many progressive policies fall outside it. One example is government spending, on which the media constantly reinforce the – economically unsound – idea that the government should run like a corner shop.

Both ethically and economically, the truth is that further austerity would be extremely damaging to the country. But a progressive politician saying this today could be branded idealistic, naïve and irresponsible. (Although some mainstream reporting has at last begun to contradict this longstanding narrative.)

The Overton window is constraining what progressives can say and their chances at the next election.

Somebody else – such as a non-party-political coalition – will need to say what the progressive parties cannot, in order to move the Overton window over the next three to four years.

This coalition could include new media outlets, experts with vital expertise that is not being properly communicated, creative artists and campaigning organisations.

Winning a majority

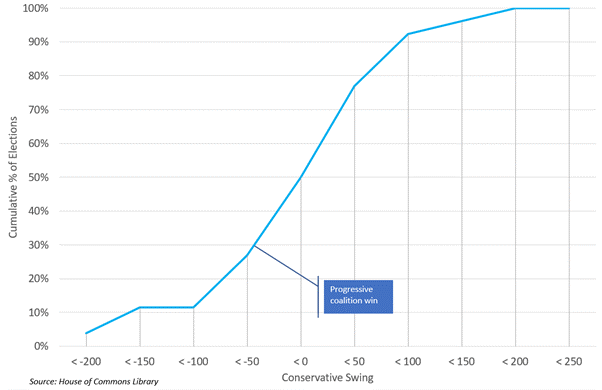

Media aside, opposition parties face an uphill struggle as a result of our electoral system. The Conservatives won only 44% of the vote in the 2019 general election, which translated into 56% of the seats in the House of Commons, giving the party an 81-seat majority.

Could this system work as well for Labour in the next election?

For Labour to win an outright majority at the next election would require a swing of over 120 seats, even before harmful boundary changes are taken into account. When we look at the swings that Labour has achieved in every election since 1918, we see that a 120-seat swing has happened before – but only around 10% of the time, and only once since 1945.

What about a progressive alliance?

For the Conservative party to lose its majority would require a swing away from the Conservatives of at least 41 seats. Similar swings have happened about 30% of the time – around three times more likely than an outright Labour victory.

So, an alliance is necessary but not, on its own, sufficient to ensure a progressive majority. We need a comprehensive progressive campaign.

Clearly, ‘business as usual’ will not be enough to secure a progressive victory. Even business as usual with an agreement for electoral cooperation may well not be.

A radical change of mindset, strategy and organisation can shift the odds dramatically. To move the Overton window, it must:

- be inclusive – and widely appealing

- innovate new forms of communication, influence and protest.

Inclusivity

With first-past-the-post, simply gaining a majority of votes is not enough. If we assume that all parties to the left of the Conservatives, and their voters, are progressive, the progressive alliance would have substantially more than 50% of the vote. Even without the ‘other’ votes it would be almost 50%. But that would not be enough.

At the last election the Conservative Party secured a large majority with only 44% of the vote. To ensure it won a majority, a progressive alliance would need the Conservatives to lose 41 seats. Past elections indicate that this will require a further 3–4% of the vote, reducing the Conservatives’ share to 40% or less. If we assume that far-right voters are inaccessible to the progressive parties, that means many of these voters must come from the one-nation tendency within the Tory party.

Creating a campaign which can appeal both to the hard left and to moderate conservative voters is far from straightforward and may not even be possible without moving the Overton window. This means that serious planning – and action – is needed immediately. It also needs a significant change of mindset: any kind of purism will not be sufficiently inclusive and will not deliver enough votes.

Innovation

Things which used to work do not work anymore; and things which were not possible are possible now.

For example, the poll tax riots in 1990 are estimated to have involved up to 200,000 people, and changed policy; whereas the up-to-twice as many people who attended the two largest anti-Brexit demonstrations in 2019 achieved little. Conversely, party political broadcasts used to be seen by the nation, whereas now we can identify tiny segments in the population with social media and tailor messages to them.

Many of our conventional ways of communicating, protesting and influencing – via mainstream media, large demonstrations, strikes – may no longer be effective. We need new ways of getting our message across – ways which make sure that those responsible for the problems are the ones who feel the pain.

A general strike nationwide or in a large city would cause hardship to those least able to bear it. A targeted denial of service aimed at the two dozen policymakers most responsible for the city’s problems would be far less costly overall, and probably far more effective.

In the same way, we need to be more innovative in the way we communicate to the population as a whole.

Lessons from the US

Not long ago, Donald Trump seemed invincible. He had defeated Hillary Clinton despite not winning the popular vote, and he governed with a disdain for all norms and precedents. He placed loyalists into all important functions of state. His core voter base grew ever more fanatical, and previously reluctant Republicans swung into line behind his presidency.

The Democratic Party, by contrast, seemed increasingly divided: split between traditionalists and supporters of Bernie Sanders. There seemed a real possibility of a united right going into battle against a divided left.

But this did not happen. Recognising that the stakes were too high for internecine squabbles, the two factions came together – Joe Biden is now the president while Bernie Sanders has the responsibility of chairing the US Senate Committee on the Budget.

The UK needs to do the same.

A longer version of this piece is available here.

The 99% Organisation is a non-party-political organisation whose prime objective is to end mass impoverishment peacefully.

Mark E Thomas is the author of 99%, one of the Financial Times’ Best Books of 2019. He has spent most of his career in business; for many years he ran the Strategy Practice at PA Consulting Group. During this time, he began to explore whether the tools and techniques of business strategy could be applied to understanding the health and stability of countries.

This research led him to the uncomfortable conclusion that many developed countries –including the US and the UK –are unwittingly pursuing economic policies which will result in the unwinding of 20th century civilisation before we reach the year 2050. Hearteningly, he also concluded that this fate is entirely avoidable.

Mark is also the author of The Complete CEO and The Zombie Economy. He has a degree in Mathematics from Cambridge University and lives in Herefordshire.

There’s a phrase I keep hearing, “but what’s Labour going to do about it?” And I always think, “wrong question, what are YOU going to do about it?”

Good to hear the same question being asked by someone who’s worked out that going on a few demos or indulging silly fantasies about general strikes isn’t going to help.