Forgive me, this is as personal as it is political.

I don’t know what to do. A world that was getting darker suddenly turned pitch black. Zygmunt Bauman is dead. The towering intellectual colossus of our times and yet such a frail, slight and humble human being is gone. He lived an amazing life and was an amazing person. The brilliance of his mind and the warmth of his heart shone so strongly and clearly that even in these bleakest of times we had a person that could light the way to a good society.

To live to 91 and do so much can’t really be sad. But I am crying as I write. Not just from sadness and feeling bereft, but out of the fear of not being able to make good what his legacy leaves us, just when we need it so much. Because Zygmunt saw Trump, Brexit and the lurch to the right happening before anyone else and he understood the weakness of the left in an age he described as liquid modern.

I first read Zygmunt properly at a formative moment, around 1998, just as I was groping towards a fundamental critique of New Labour. He helped me understand that the role of the poor isn’t just to be a reserve army to be called on when, and only when, the economy needed them; they existed to be humiliated and ‘Othered’ to police us to run endlessly on the treadmill of turbo-consumption for fear of being like them. As I watched New Labour divide the ‘deserving’ from the ‘undeserving’ poor, it was like a thunderbolt to my political soul.

And then, digging deeper into his work, I grasped his insight into the shift from a world based on our identities formed by production, to identities, life and a society formed largely by consumption – buying stuff we didn’t know we needed, with money we don’t have, to impress people we don’t know. And then the separation of politics from power and power from politics, as financial flows and corporate investment escaped the nation state and went global. All this and more drew a line under under the solid and predictable culture of the 20th century and hurtled us into the fragility and fluidity of a 21st Century culture where everything feels temporary and until further notice.

So Zygmunt understood the crisis of social democracy whose success was rooted in solid jobs, fixed identities and bounded within nation states. And so he paved the way for our thinking about the need for progressive alliances, not just of parties, but of movements that are trying to negotiate and navigate a world in which each day we live the tensions between our need for security and our desire for freedom.

Reading Zygmunt can be tough – both in terms of the language but also the bleakness of his some of his analysis. Some recoil. But staring into the abyss is the only way we prepare ourselves for the fight ahead.

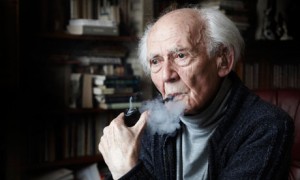

For me, there will be no more vodka at noon at his ramshackle home on the edge of Leeds, where he was Emeritus at the University for longer than he was employed there. There will be no more billowing pipe smoke as he pondered on what pearl of wisdom he was going to nudge you with next. There will be no more insightful articles (like these at Social Europe) or precision-bombed speeches and interviews shining his torch to the future. Momentarily there is a void. And we have to fill it. We will do so by taking his ideas, his insights and his enormous appetite for humanity and building and shaping them.

Zygmunt knew that we don’t die wishing we owned a bigger television, but longing for more time to be with the people we love, doing things we love doing. It is how he would have died. He never stopped. He never gave up. He said the ‘good society was one that didn’t know it was good enough’. As a member of Compass, he knew everything was about the journey, our sense of direction and the way we behaved towards each other as we travelled the road to get better and better.

In the bleakness of our moment, and the sadness of our loss, I am so grateful for what Zygmunt Bauman gave us – hope. Now we must act on it.

Our current government spreads the message that all poor people are deserving of their situation. Dennis Skinner was absolutely right when he said that since Cameron came to power he has aimed to divide the nation between “strivers and scroungers”.